1v3D

Copyright 2022

The Physics of Boids

Simulating Boids appears to have become quite a common coding exercise and is well covered, both as great YouTube content and extensively across blogs, so I had not planned to add my own take on it when I started to explore the seemingly simple set of rules that yield complex and organic looking visuals of emergent flocking behaviour. After diving deeper into the topic, however, most sources of information on the topic appear to focus on the classic set of 3 rules, performance optimisations and, if you’re lucky, a list of ‘magic’ coefficients to make it work, which didn’t sit well with me.

In this article I hope to provide a more intuitive framework for the Boids simulation, simplifying the rules and provide a reasonable argument for how rules combine in a more forgiving and intuitive way.

Boids Overview

Rules

Before introducing my own take on the rules and the corresponding physics-based framework, I want to start with the core concepts of the Boids simulation introduced in 1987 by Craig Reynolds. The original paper proposes that in order to simulate organic and complex flocking behaviour, similar to what you may see with certain kinds of birds and fish, only a simple set of three rules are required that each participant, or boid, follows:

- Centring - Stay close to centre of the group of every other you can see around you

- Matching - Match your velocity to those you see around you

- Avoiding - Avoid getting too close to those you see around you

Although sufficient to achieve a realistic looking flocking behaviour, in almost all practical cases certain boundary conditions exists, e.g., when leaving one side of the space the simulation runs in a boid is ‘warped’ to the opposite side, but more often boids are diverted away from the simulation boundaries in a similar way they might avoid other objects, creating an optional but often implemented 4th rule:

- Dodging - Dodge boundaries and objects to avoid a collision

These rules are then combined in a weighted manner, with weights generally found by trial-and-error until the result is visually pleasing. The process of finding these weights can be challenging, because three forces need to be balanced at the same time.

Parameters

Every Boids simulation takes place inside a certain simulation volume and / or at a certain scale, which will contextualise aspects such as the size, position, velocity, etc. of each boid. For example, in the simulation I wrote, each boid was displayed with a bird-like model, having a bounding box of around 10x10x10 units inside Unity. Which can be used to start to set the main set of variables that control the main visual aspects of a Boids Simulation:

- The range within a boid will try to avoid others:

- The range within a boid can see others:

- (optional) The fraction of the field each boid can see:

I ended up simulating a volume of

Schematic Overview

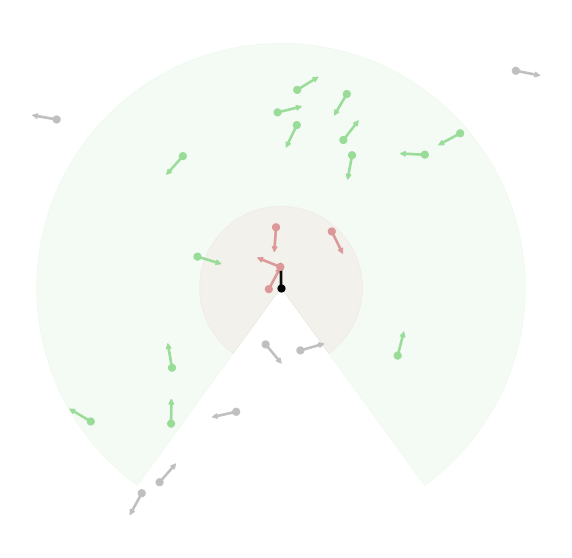

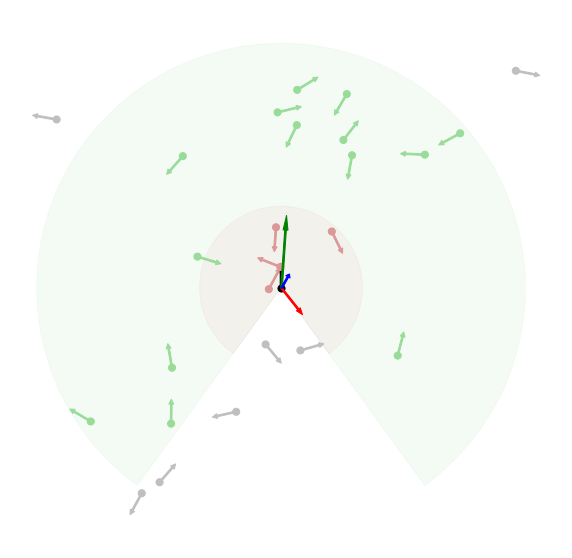

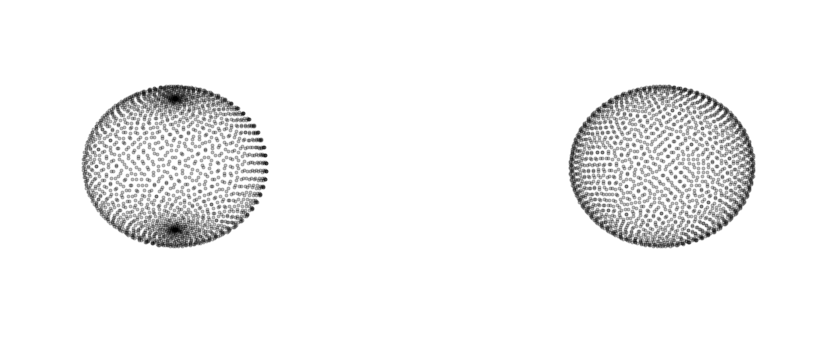

To explore the impact of each force, I’ll be using an abstract 2D representation for one boid as shown below, with

Physics Based Framework

Centring

Most simulations will have one force to nudge each boid to the centre of mass and another to nudge the direction of travel towards the average direction of their visible neighbours, however, it felt more natural to me to combine these two rules into one and nudge each boid toward where the centre of mass will be in the future, given its current position and velocity. It is in essence almost the same thing, but the relative importance between the position and velocity of the group has now a more intuitive meaning. I also found it more natural to assume that animals that show flocking behaviour would instinctively aim for where the others will be in the future instead of where they are now, similar to how a person would throw or kick a ball ahead of another player in sports to account for the ball’s travel time, instead of correcting for both aspects separately.

To know what amount of acceleration is needed to move a given boid (i) to the Centre of Mass (CM) of the other boids it can see, I assume a simple extrapolation of the current location of the CM and the boid itself, with

The equation for the acceleration (or force for a mass of 1) that will nudge a boid towards the future location of the centre of mass (CM) is very similar to have force for the location and average direction separately, with the velocity component weighted by a factor of

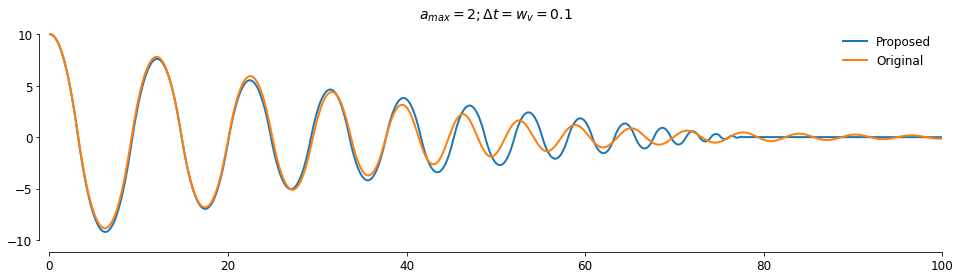

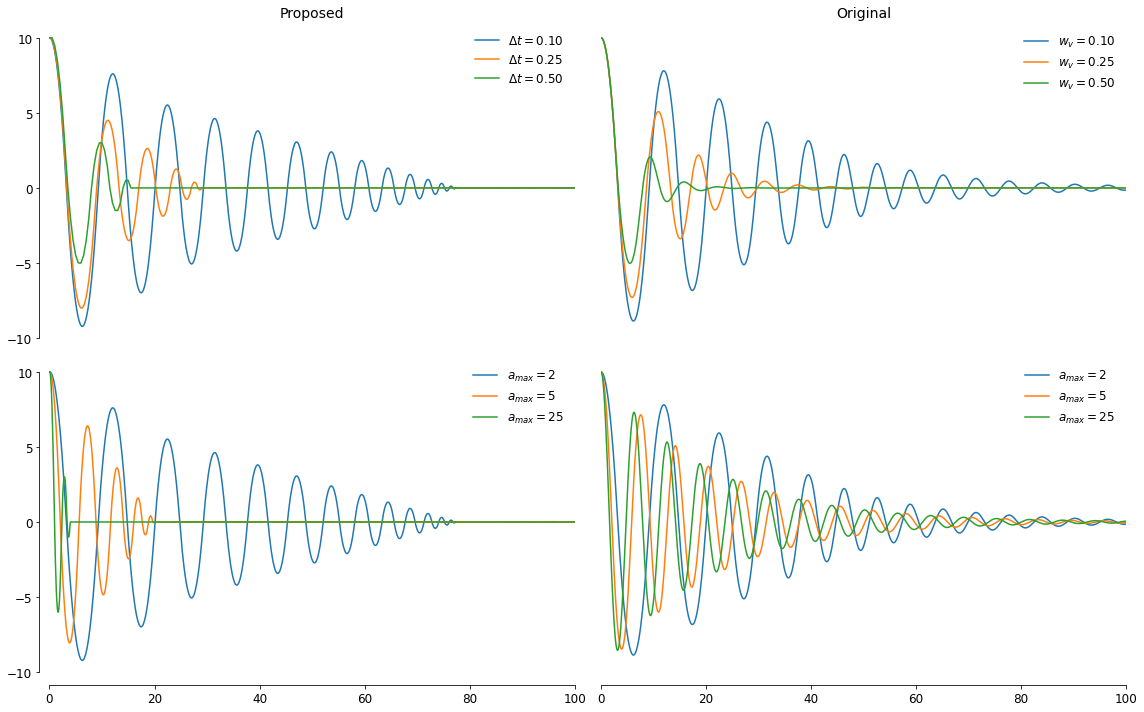

Note that I’ve used here a cap on the maximum acceleration that can be achieved, because the proposed version will otherwise asymptote almost immediately since the applied acceleration is almost exactly what is required to arrive at the CM at

To illustrate the impact of and get a feel for changing the

Avoiding

For avoiding other boids, I found a variety in treatments in online available sources but most fell into broadly two categories: Proportional to the distance or the reciprocal distance, and practically all are adding the forces from all nearby boids to avoid together, making the net force depend on the number of boids that are ‘too close for comfort’. Especially that last part didn’t sit well with me, because an animal in a flock would not start moving twice as fast just because there are two others nearby vs. only one at approximately the same location. In the end I landed on a similar approach as I used for the centring force, by calculating a weighted Centre of Mass to move away from. The weighting is based on how close the others each are

Solving a similar equation as eq. 1, where the ideal amount of acceleration is based on what it would take to move away from this weighted CM, similar to eq. 2:

where the

where

Combining Forces

With eq. 2 and 3, the net applied acceleration can be calculated for each boid, capping the magnitude at a given

With the two accelerations in hand, it is also possible to re-balance their importance for the boids, mixing them with

Extra Rule: Object Avoidance

Object avoidance is an important aspect of any flocking / boids simulation, if anything to keep all boids inside a certain volume for visualisation purposes. The original paper describes a process to find a direction that deviates the least from the current direction of travel and is unobstructed. To find this free direction to move towards, I used a common ray casting technique where you start in the ‘forward’ direction of the boid and then iteratively increase the pitch by a small amount, and the roll around the travel direction by an amount that minimises repetition. A common value for the latter is the (inverse) golden ratio as the most irrational number. In spherical coordinates:

The acceleration needed to avoid a collision then becomes:

which can then be mixed in with the other two forces. For experimentation, prioritising the obstacle avoiding above all else gives the best results, and a mixture of 50% obstacle avoidance 49% boid avoidance and 1% centring gave me robust flocking behaviours in a 3D simulation. Below is a video capture of the simulation, but the quality is quite poor due to the challenge with video compression of lots of small moving objects while trying to keep the file relatively small:

Note that for the simulation shown in the video I did not add a dominant initial direction to the boids, counter what appears to be common practice, to emphasise the interaction of the forces when the global CM is not moving much.

Conclusion

Based on these explorations, I feel that a system of equations rooted in a more physical approach has value for Boids simulations, making the choice of parameters that govern the visual effect less opaque. That said, I’ve not seen anything that leads me to believe either approach produces more pleasing visuals than the other. Hopefully this approach can be helpful to others that look to explore creating a Boids simulation in the future and, if anything, shorten the amount of time needed to find the right balance of influences on each boid to achieve the desired visual effect.

This page has been converted from a Jupyter Notebook with most of the code removed for an improved reading experience, however, if you are interested in reading through the code behind the plots and / or playing around with the original notebook, it can be downloaded here. The simulation I created in Unity for this exploration didn’t feel sufficiently interesting to share as a standalone build, but if you are interested in using the source code for your own project, feel free to reach out.